By Sanjay Datta, Chief Financial Officer at Upstart

An abridged version of this article originally appeared on Fortune.com.

These days, bring up the subject of the economy, and you are most likely to elicit a shrug. No one exactly knows what to make of it. Are we in a recession? Or not in a recession but about to enter one? Or did we narrowly avoid one and achieve the oft-discussed “soft landing”?

Opinions abound, but no consensus:

Mostly, it is confusing. What gives?

Well, the modern recession playbook generally goes something like this:

- Cue some external shock (like a spike in oil prices, a dot-com bubble, a savings & loan scandal, or a subprime mortgage crisis. We are inventing new ones as we go).

- The financial markets seize up—interest rates rise and financing becomes scarce.

- Firms invest less as financing becomes more expensive; consumers consume less as credit becomes less available.

- GDP contracts; firms lay off workers and unemployment rises.

Once you hit the daily double of contracting GDP growth and rising unemployment—bingo! You have yourself a classic recession.

So, is this happening today, or not? Well,

- We’ve had quite a shock. (hint: inflation)

- Financial markets have seized up, right on cue—interest rates are up, and financing is hard to come by. But…

- …even though some high-profile industries have conducted layoffs, unemployment has barely budged! And…

- …consumers aren’t consuming less—they are somehow consuming more! (And defaulting a lot more on credit.)

How do we make sense of these seeming contradictions? How can spend and production be growing so quickly in the face of such high rates and prices? Why are so many consumers defaulting on credit when almost anyone who needs a job can find one?

While we are not presumptuous enough to enter into the fray of economic prediction (“The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.” —JKG), we can survey the raw data together and draw some interesting insights around how we are collectively working and spending money.

Money makes the world go round

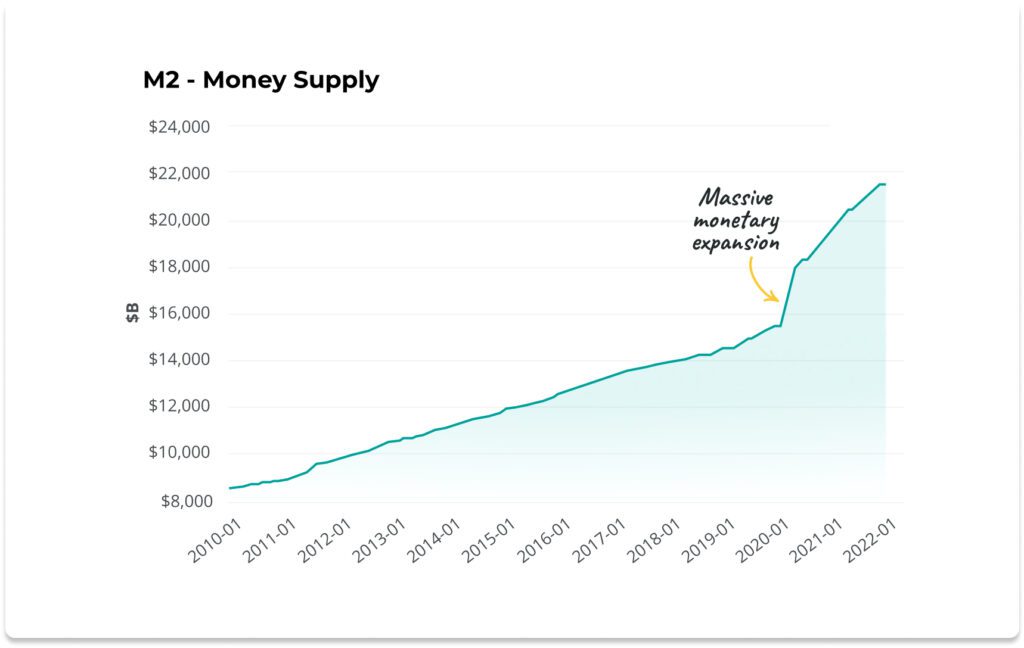

Much of today’s economic fog of war seems to have materialized in the wake of the pandemic—and, of course, the enduring economic legacy of the pandemic was a healthy dose of government stimulus. So as a starting point, it is worth reminding ourselves that the stimulus was, like, really big.

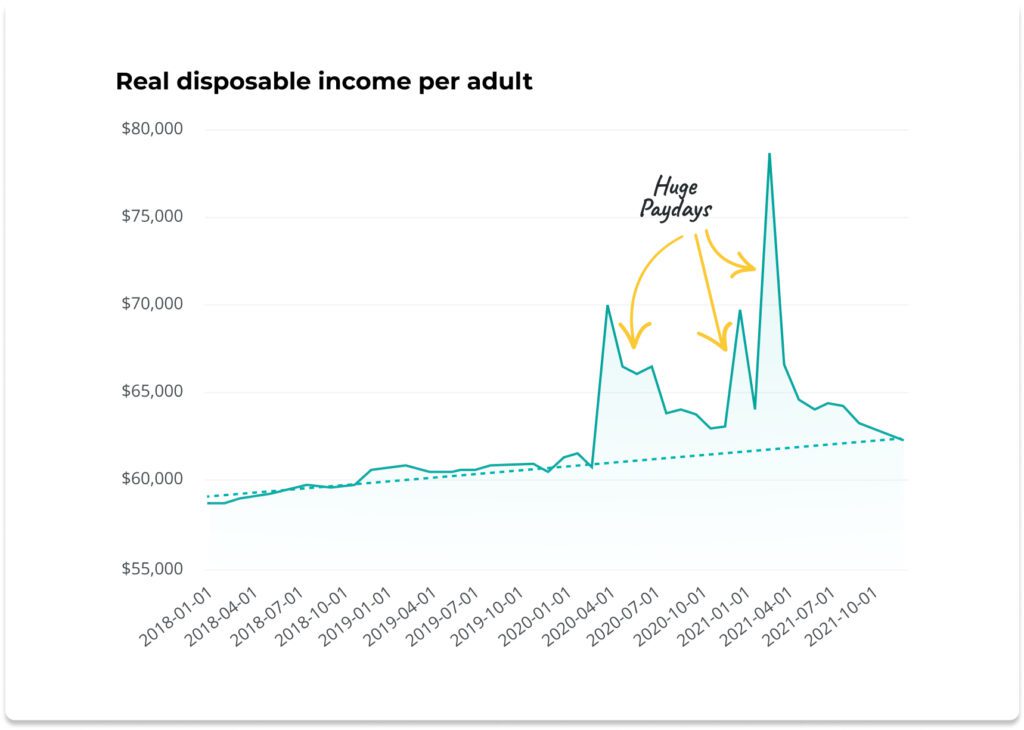

Just prior to the pandemic, the amount of money in our economy (in our savings accounts, under our mattresses—in this case, what economists refer to as M2) had gradually grown to just over $15 trillion. Post-lockdown, a mere two years later, M2 had ballooned to almost $22 trillion—an increase of almost 40% in the amount of money circulating in our economy. This massive influx of money ultimately made its way into our pocketbooks via the rather large incomes that we were, on average, earning during those two years:

So, from an income perspective, the years 2020 and 2021 were effectively boom years in which we collectively earned the equivalent of a string of extremely large bonuses. No wonder we entered 2022 feeling rather upbeat! Inflation (and war) were not yet on the radar. Combined with rising asset values (see: NASDAQ, Bitcoin), the initial post-lockdown years were, in fact, years of great affluence.

So what did we do with this affluence? Well, a few things that in hindsight should not be surprising. The first, is that we kinda took it easy.

Looking for a few good people

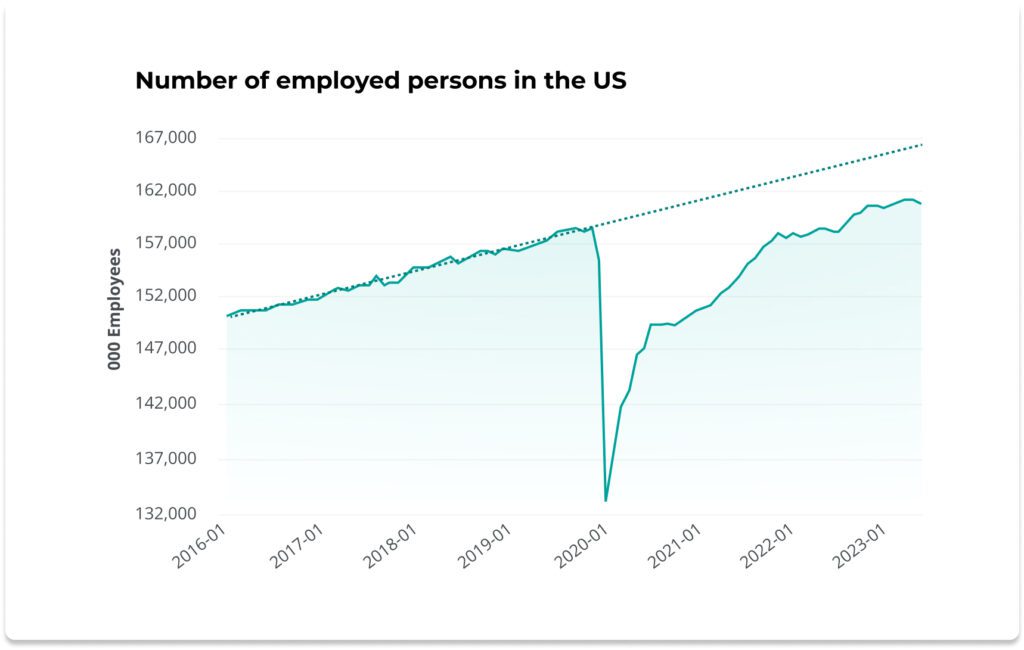

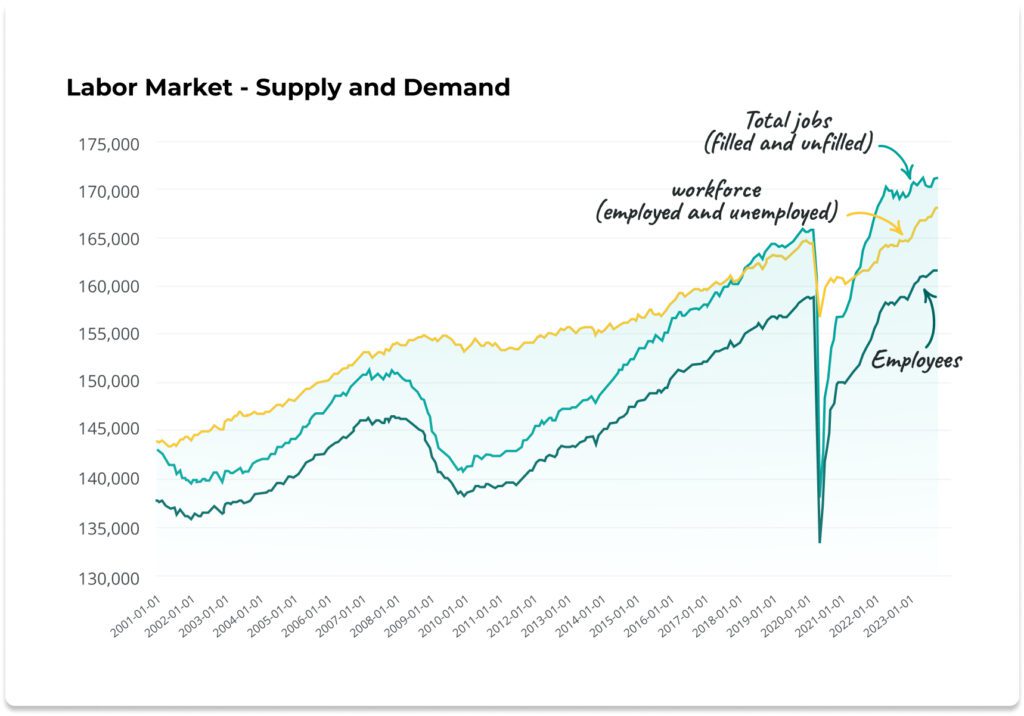

The number of people employed in the U.S., which had grown steadily since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), made a very half-hearted initial recovery from lockdown. Since then, Americans have steadily trickled back to work, but even today we are still 5 million or so workers short of where our labor market was heading pre-pandemic.

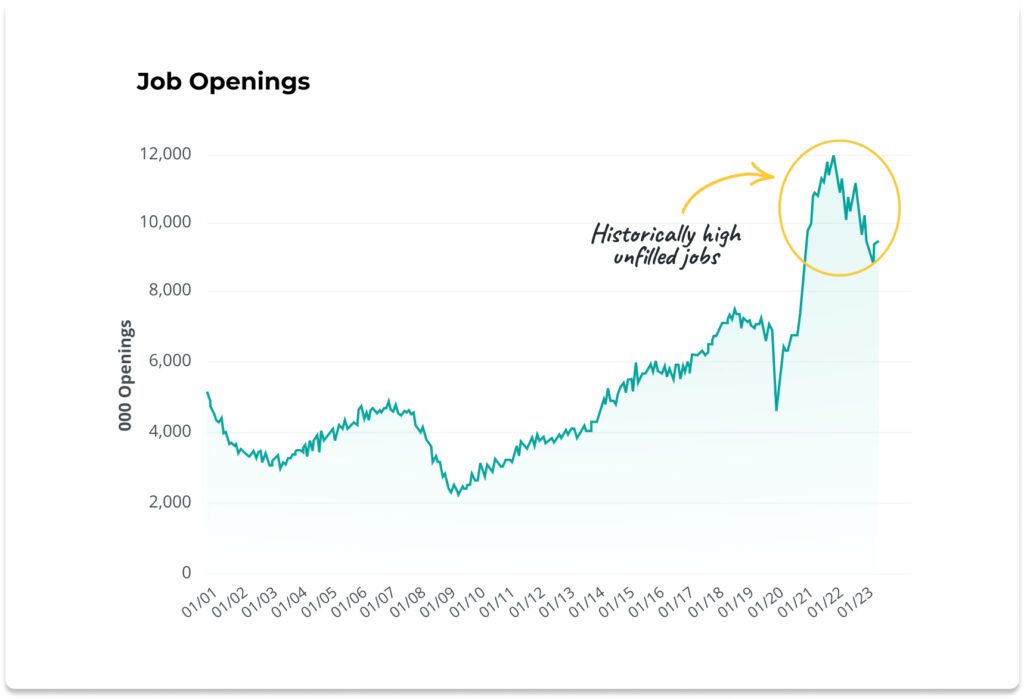

Why is this? Are the workers no longer needed—are we just making and selling less stuff—or are workers needed but simply no longer interested in working? Well, real levels of consumption and production in the economy keep scaling to new heights, so presumably workers are still required to support that. One glance at the unfilled job openings in the economy should be enough to convince us of this.

The exit from lockdown created a record need for 12 million workers for jobs that weren’t getting filled. Even as America has trickled back to work, we still today sit at an unprecedented level of job openings (just over 9 million)—some 4 million to 5 million above the typical run rate of the economy. There are only around 6 million people in the entire country even looking for work at all—We could put them all to work tomorrow and still have a relatively “normal” number of unfilled jobs postings in the economy. This current shortage of workers represents an extraordinary scarcity in the U.S. labor market.

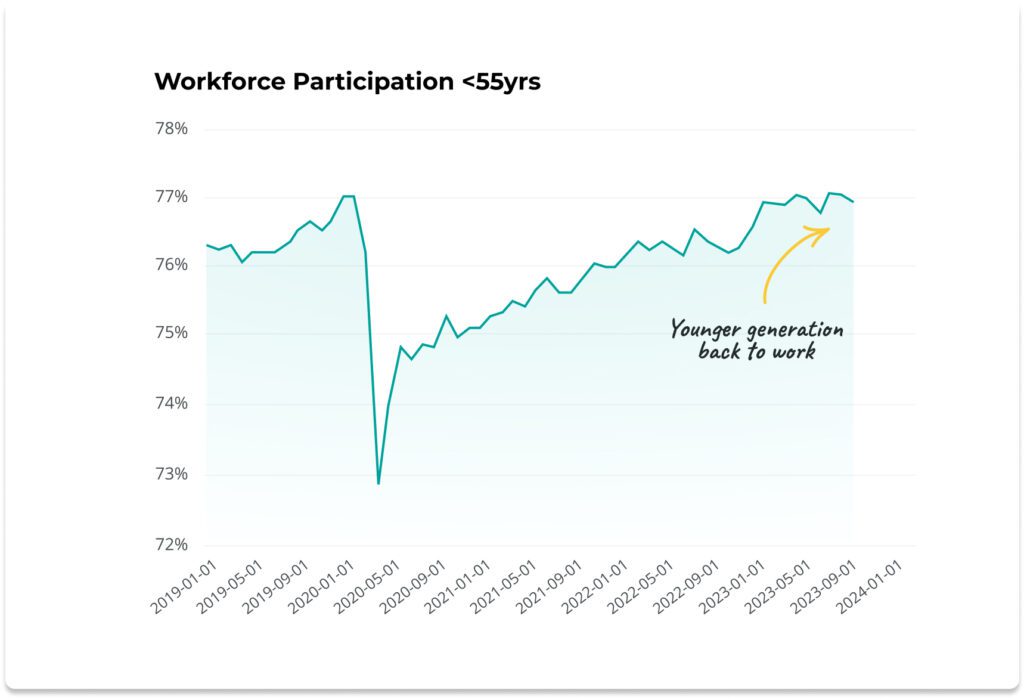

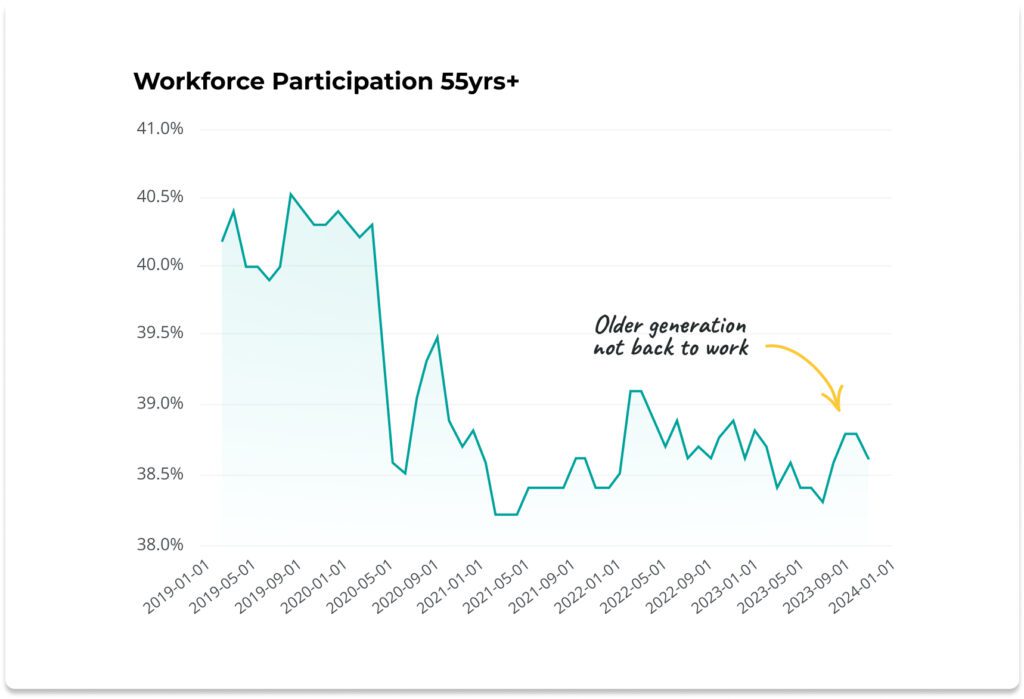

So, workers are needed, but for some reason they are not working. Who is staying on the sidelines? It turns out that, far from the headlines of millennials quiet-quitting and great-resigning from their jobs, the younger generations are almost fully back at work, and it is the older workers who are not budging from the comfort of their empty nests.

It is tempting to conclude that COVID pushed a significant number of workers into early retirement, and hence our labor market into a supply shortage, and this view is not entirely incorrect—but it is not the whole picture. In the grander scheme, the pandemic merely accelerated a structural problem that was already brewing. Production in our economy has been steadily growing at a 2-3% clip for the last few decades; our adult population has been growing at less than 1% over the same period. That is only sustainable for so long, without large ongoing shifts in immigration or productivity. The main way our labor supply kept up with the brisk economic expansion of 2010-2020 was by steadily whittling down the unemployed from 10% to 3% of the labor pool, even against the headwind of declining participation from an aging workforce—but by the end of the decade that squeeze had run out of juice, as we approached full employment.

By the time of the pandemic, the total number of jobs in the economy (filled and unfilled) had already begun to outstrip the overall size of the workforce, for the first time this century. Even notwithstanding the interruption from COVID, it is not clear at those growth rates where the next wave of workers would have come from to support the continuing ramp in consumption of an aging population. The pandemic, by nudging many of the older workers out of the labor force, has accelerated this demographic mutation and amplified the current historic imbalance between the demand and supply of workers.

So, income associated with the stimulus coincided with a reduction in work effort, at a time when labor shortages were already encroaching, leaving us with a large shortfall of workers that almost any small business today is experiencing viscerally. And, also concurrent with stimulus, was the other notable (and unsurprising) thing we did with all of that income, which is that we bought a lot of stuff.

The Consumer Rules

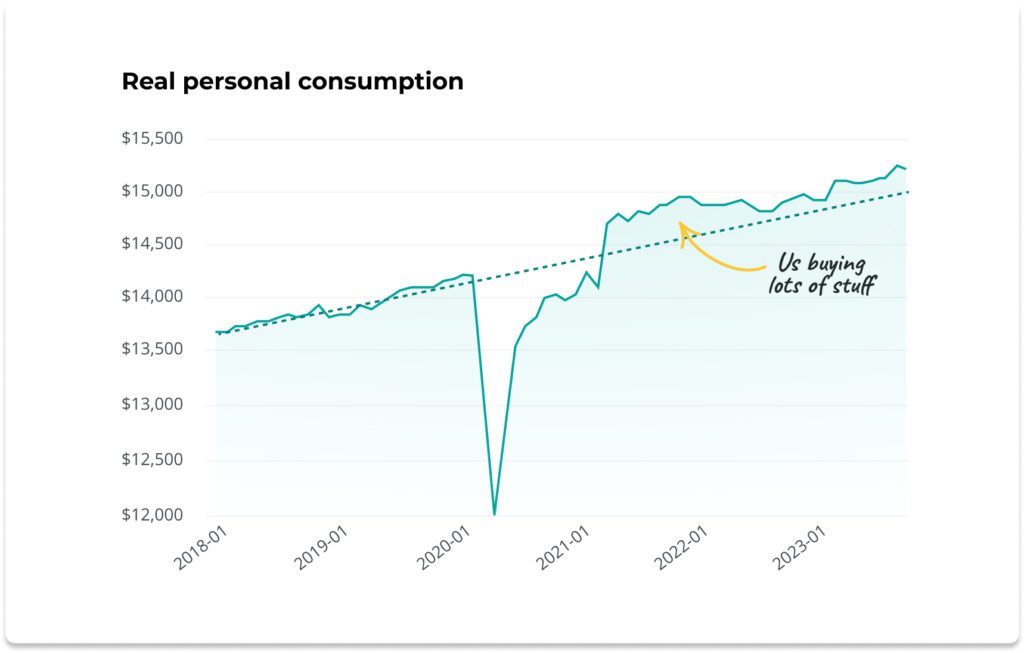

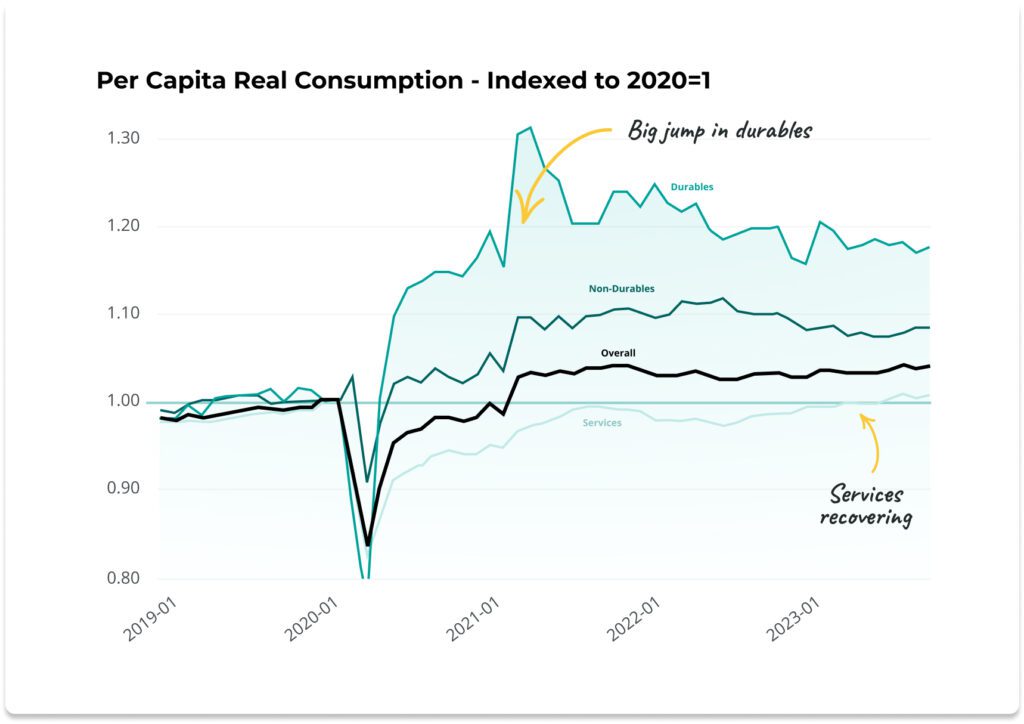

By 2021, our nation’s consumers had emerged from lockdown and recommenced purchasing as if nothing had ever happened—in fact, accelerating even beyond the pre-COVID trajectory. The most eye-catching subcomponent of this trend is that our consumption of durables immediately shot up by almost 20% (after adjusting for inflation) post-lockdown relative to pre-pandemic levels, and has largely sustained. Durables are, of course, bigger-ticket items that we tend to purchase with excess disposable income: Think cars, electronics, home appliances, furniture and jewelry.

So, we have been enjoying quite a nice buying spree of (relatively expensive) discretionary items, which shows no obvious sign of letting up. More recently, the larger service economy has also started to recover, bringing more fuel to the consumption boom.

But the stimulus checks stopped coming back in 2021, so how has our income kept up with the pace of real expenses in 2023 to sustain this consumption boom? It hasn’t.

Keeping up with the Joneses

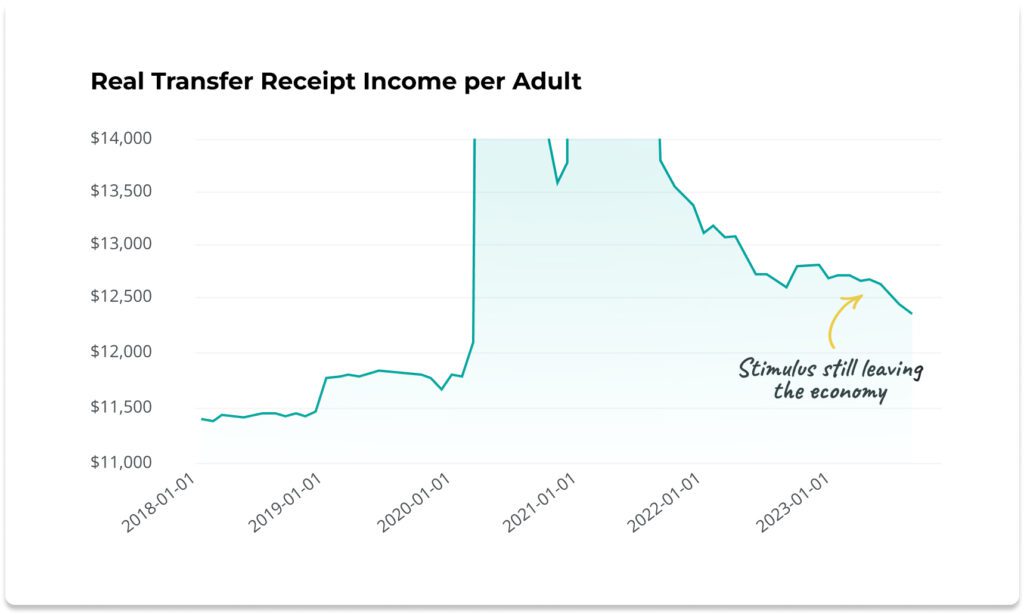

Relative to their pre-pandemic relationship, income growth has not kept up with our torrid pace of consumption. The return to work has been lethargic, and any gains from higher aggregate employment compensation have been offset by the headwinds of higher tax burdens (in 2022, from all the money we made in 2021), and then from stimulus continuing to drain from the economy. That’s right—even today, stimulus continues to be injected into the economy at a level roughly 8% higher than pre-pandemic (in economist speak, the category of transfer receipts, which are essentially income we receive from the government in exchange for doing nothing). As that level of stimulus keeps dissipating, it is impeding our incomes from rising to meet the demands of our updated consumption patterns.

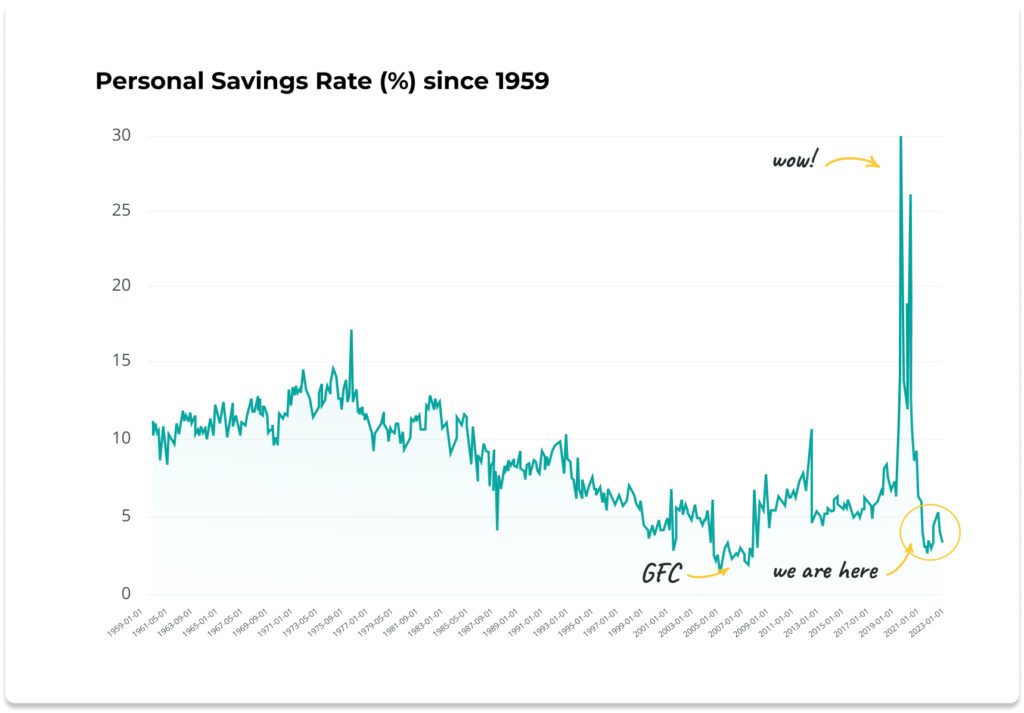

This growing imbalance between our consumption and our income has strained savings rates to their lowest point in 65 years. The only other prior comparable period was indeed in the wake of the GFC. Of course, back then the root cause of our precarious fiscal health was income-related, from the stress of 10% unemployment. Today, it is surely not that. It is instead self-wrought, from our choices around consumption relative to the incomes we are consciously earning.

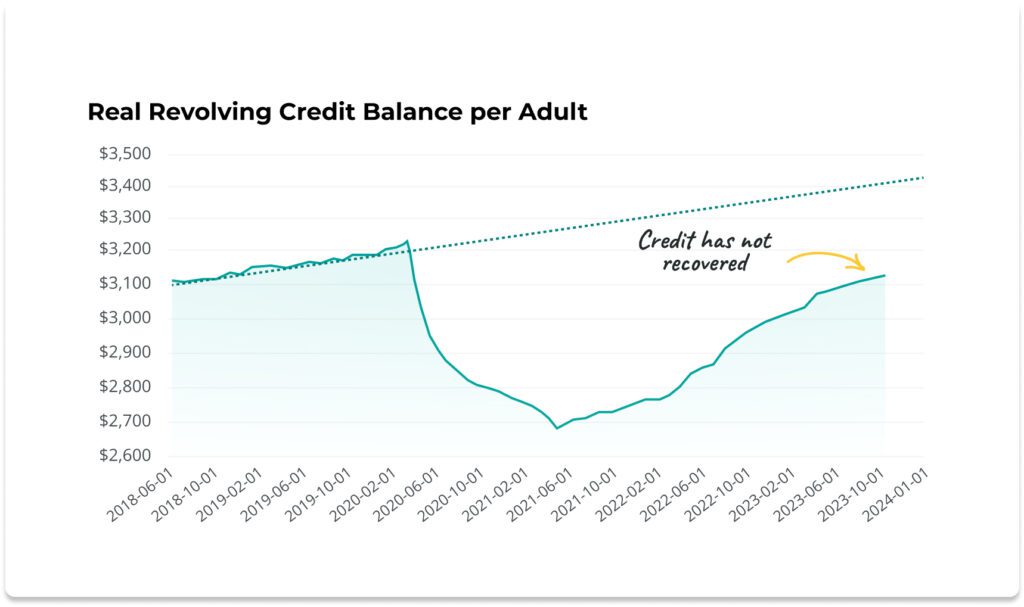

So how then are we sustaining this level of consumption that appears to be beyond our means? Despite headlines about the record level of revolving consumer debt, the reality is that when adjusted for inflation, real per capita levels of revolving debt have not recovered to where they were pre-pandemic. So this does not appear to be a credit-driven consumption boom, which is likely one reason high interest rates have done little to dampen it.

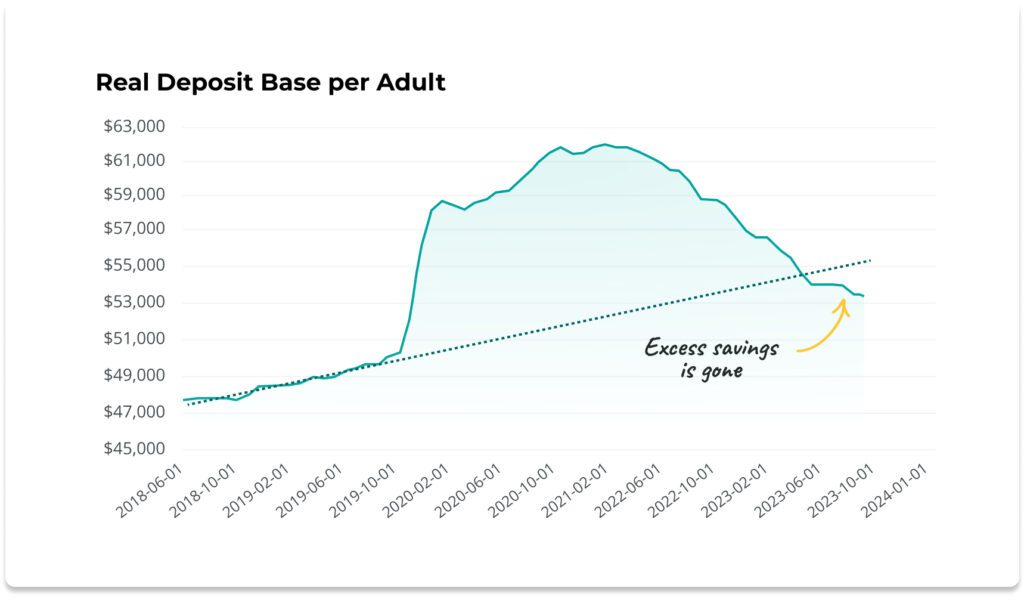

The fuel for this consumption has instead come via the excess cash saved from the stimulus, which has lingered in our bank accounts for quite a while but at this point is now largely spent. This quick expansion and sharp contraction in the deposit base is also a historic anomaly, and very central to the struggles that our banking sector has experienced over this past year. Banks aren’t easily able to quickly unwind assets in response to a spenddown of their deposit base, and in the recent history of the U.S. deposit base, they have never had to worry about one at this speed and scale.

Where do we go from here?

Taking care to avoid wading too far into the business of prognostication, a few things are observable about the present and recent past:

During the pandemic, the government injected a massive amount of money into our economy.

The subsequent windfall induced us to dial back at work—particularly those workers closer to retirement—exacerbating a pre-existing demographic current which already had us drifting towards a structural deficit of workers.

Meanwhile, we used that money to buy a lot of durable things, a habit which we now seem loath to abandon.

That excess cash from the stimulus has lingered in the economy and funded our spending spree for quite some time. Interest rates haven’t put much of a dent in these new spending habits because we haven’t yet needed much credit to sustain it. But, the excess cash from savings is now gone (to the chagrin of the banking system).

The core “recessionary” shock currently on the table—inflation—should not have come as a surprise to anyone. A 40% increase in the money supply will generally wash its way into the price level. Fortunately, this was a (big) one-time-ish thing, and inflation is slowly but surely subsiding.

Nor has this shock yet resulted in any economic contraction or unemployment, because of the excess cash left over from the pandemic (sustaining our economic activity), and because of an emerging reality in the labor market where workers are just generally harder to find, maybe permanently.

As prices have jumped and the excess savings from the stimulus fades from view, we are running very thin on aggregate savings. This is causing a surge in consumer defaults across products, segments, and industries. People will eventually have to put their fiscal affairs in order, and adjust budgets and expense calculus to reflect the new nominal price level, and to the dwindling stimulus checks that we had only recently gotten so used to. The good news is that there are jobs right now for anyone who wants one.

So—is all of this commotion pointing us to a looming recession, or are we now in the clear?

We, of course, have no idea. But, somewhat counterintuitively, we are secretly hoping for one. A mild one. Kind of.

Let me explain.

The current predicament of our economy is that we are consuming too much stuff relative to our paychecks. Consumer fiscal health is on thin ice, with little savings buffer, at a time when prices are unpredictable and non-employment income shocks (from higher taxes, lower transfer receipts, etc.) are volatile.

We need to rehabilitate our savings rates and balances in order to restore stability to personal finances. A dose of economic anxiety might be the nudge we need to make those adjustments, and return to more sustainable levels of consumption.

A reduction in consumption would of course likely imply a contraction in GDP, and this will technically be called the R-word. But viewed through the broader lens, our central problem today is indeed that GDP growth has been running too high for our means. So we would view this version of a “recession” as a welcome normalization.

An important caveat, though, is that while recessions are traditionally accompanied by rising unemployment, today’s labor market is in the midst of a structural transition, where the supply of jobs has now outstripped the size of the entire workforce, even as consumption continues to outgrow the adult population. While a contraction in GDP would certainly eat into today’s excess supply of jobs (and hopefully nudge the labor market closer into balance, even if a little bit past it), we believe under current circumstances that it would be unlikely to flip the excess supply into a meaningful job shortage, causing significant enduring unemployment. So in silently pulling for a slowdown in economic activity, we remain relatively sanguine about the employment risk in such a scenario.

Our ultimate view then is that the benefits to consumer health from a more moderate level of consumption (even if technically recessionary) are more than worth any ensuing risk of significant unemployment; both because the probability of such an event is now relatively low in our opinion, as well as the fact that the government is now well positioned to combat any unemployment that encroaches. Certainly, there is ample room to reduce the now-high interest rates to support consumption in the event that it deteriorates too much.

And of course, as we’ve discovered over the past few cycles, we can always turn to the option of introducing more monetary stimulus into the economy if things become very dire, a move that seems to have worked quite well in countering the most recent unemployment crisis in 2020. Although, as we have shown, clearly the costs of taking such an approach are still in the process of being understood.